Cam Bohicket

Wilderness Calling

Is your woods healthy?

A homesteader’s goal is not just to provide food, but also to live in harmony with the Land, nurturing it into balance. But there’s a problem: most American forests nowadays are missing a key factor.

Before the colonization of America, explorers described the landscape of the East Coast as being an open savannah, filled with berry bushes, pasture, nut trees, and prairie plants on the forest floor–a paradise for game animals and all biodiversity. In those days, buffalo, elk, deer, sandhill cranes, red wolves, panthers, black bears, passenger pigeons, and heath hens used to roam over the plentiful garden-like landscape. Take a look at the average American forest nowadays and you’ll see something altogether different: a pure thicket.

Now, the heath hen and the passenger pigeon are extinct, and all the others on the list were severely decimated almost to extinction. They survived only out West or in the East by taking refuge in little wild nooks and crannies far away from people. Thankfully, in recent decades, many of these creatures have begun to gradually spread back eastwards. Eventually, with care, our Land could fully recover.

But what happened?

What can we learn from history and ecology that would show us what went wrong and how to fix it—on our own Lands?

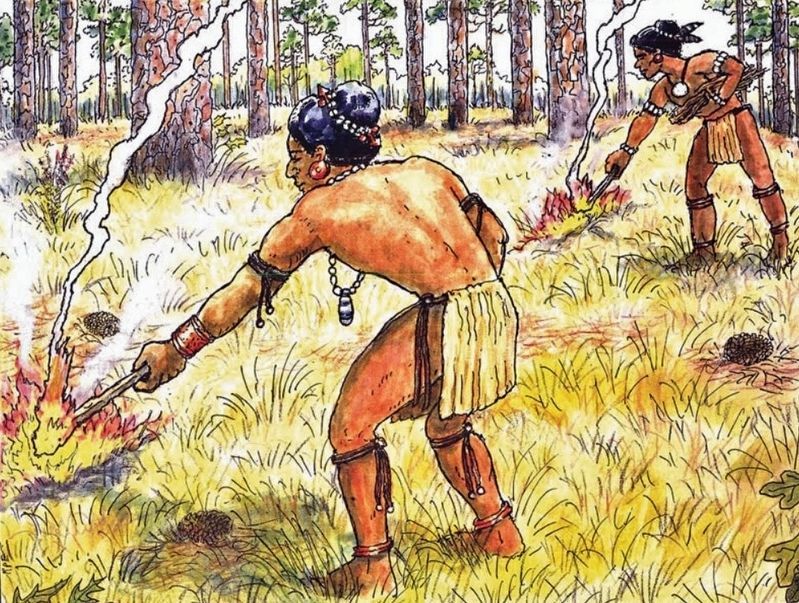

This beautiful savannah landscape was not created by accident, it was actually maintained by Native American tribes. Unlike what many people would have you believe, we humans don’t necessarily have to be a parasite upon the Land that always takes and never gives, and our highest goals for our land need not just be reducing our environmental impact. No, recent research has led many Anthropologists and Ecologists to the conclusion that Native Americans were actually a “keystone species,” in other words, they were the vital pillar that held up everything above them, but when that pillar was removed, the whole ecosystem collapsed into chaos.

On a more positive note, I’ll tell you what the primary contribution Native Americans (and early White pioneers) provided their Land: it was fire. Wildfire, unlike its conventional portrayal as a destructive natural disaster, only becomes damaging to vegetation when too much leaf litter accumulates in the forest. Thus, it requires frequent controlled burns to prevent it from getting out of control and becoming a blazing inferno. It seems counterintuitive to suppose that fire prevents wildfires, but it makes sense if you think about it. Native American controlled burns actually did not damage the trees and bushes for the most part because native plants are adapted to frequent fire–and thus burning is one easy way to weed out invasive plants and kill disease-ridden ticks.

This culture of controlled burning allowed them to rapidly integrate plant nutrients into the soil for farming and get rid of underbrush. It allowed them and the animals to more easily travel and hunt in the open forest. It enriched nut and berry production, allowing animals such as the now-extinct passenger pigeon to flourish (the thicker forests that result from fire prevention likely contributed to this bird’s extinction). It allowed big grazers to roam the Serengeti-like savannas. It even affected the environment in more subtle ways such as increasing the longevity and growth of certain fire-adapted plants, allowing the germination of plant seeds that need fire to sprout, darkening the color of the soil thus causing Springtime temperatures to be slightly warmer and prevent late frosts from destroying fruit blossoms, and much more.

A growing fear of wildfire and extreme logging of primeval, virgin, old-growth forests across the country in the early 1900s, then severe pollution and urbanization across the country nowadays have further disturbed our delicate ecosystems.

The buffalo and elk that once roamed over the whole East Coast could now hardly fit through the thick underbrush that exists in our forests. Fortunately, the US government’s long-standing policy of fire-suppression has begun to pass away as people realize the value of this wonderful indigenous practice!

Most of us would agree that our hunter-gatherer ancestors had the ideal way of living harmoniously, healthily, and lightly off the land. But for the above stated reasons in addition to a toxic and polluted environment, habitat degradation, urbanization, and species extinctions, reductions, and extirpations, our enormous modern population simply could not be supported on such a lifestyle. But there is hope!

Even though most of us can’t live as hunter gatherers, there is a solution: Landmedicine. Landmedicine (or my more sophisticated term: Pyrosilvopasture which means “forest pasture maintained by fire”) is a term I use for a type of farming intended to supply a farmer’s needs, while also helping wildlife and enriching and healing the Land. Essentially, you are filling the land with whatever it may be lacking. You’re a Land Doctor!

So how can you try all this out on your land?

Basically, most of the Earth’s land area is adapted for big grazers like buffalo to move through and mow down the grass. Of course, overgrazing can lead to the elimination of some plants in your pasture, leading to less diversity of nutrients for your livestock. Cows, though not quite the same as buffalo, make a nice replacement. Most people (including myself) would have trouble affording cows, so why not start by bringing some goats, hogs, and poultry on your land? Some people like to have a homestead based entirely on poultry: they’re cheap, they have a lot of variety, and can provide all of your livestock needs. Think of it: geese, chickens, guinea fowl, ducks, Narragansett turkeys, and more. These alone could do a pretty good job of grazing down your pasture!

Anyhow, the process is pretty simple. First, start with a piece of land, then get ready for a controlled burn during a dry season. You can do it without government permission if you’re way out in the backwoods, but you may want to research your local regulations and give a heads up to the authorities. It’s important to be careful not to start a wildfire, or you may end up in hot water. A solution to that is asking the permission of your state Department of Natural Resources beforehand to protect you, perhaps even hiring a “burn boss” to cover you even more.

Girdle the tree trunks of some undesirable or unhealthy trees in order to allow enough sunlight to reach the forest floor. Girdling means to use an ax to chop the bark off encircling the base of the tree; it is an old-fashioned way to open up forest to get more sunlight to the understory without having to cut down the tree; and as the tree dries out, it’ll provide you with plenty of firewood, too! Spread the cut-off bark out in your future garden plot. Then chop down any troublesome thorn bushes, invasive plants, and other brush (except for useful plants), and spread it out in the area you intend to burn. Rake leaves from the surrounding area and pile them on top of your plot. Raking the leaves away from around your plot will prevent the fire from spreading into the rest of the woods. If you want, you can also dump water around the edge of the fire as well. When you’re ready, light it on fire, monitoring it closely. In the end, you’ll end up with lots of ash and some charcoal. Break up and crush the big pieces of charcoal and spread them all around your garden plot. The ash is very fertile, but the rain will quickly wash the nutrients away. On the other hand, spreading a large amount of charcoal on the garden will cause the nutrients to absorb into the charcoal, keeping it there for hundreds of years to come (this is what some Native American tribes in the Amazon rainforest did: it’s called “Terra preta” and it has been revered as the richest earth you could possibly have).

Your ground is now loosened up,

covered in fertile soil and ash, the weeds are suppressed, and it is ready for planting: no tilling or plowing needed! White clover seed is a good idea to plant in amongst your crops because it is a legume and will bring nitrogen into your soil, it also is a good ground cover because it won’t grow too tall and shade your plants. Remember, though, weeds are not always your enemies! Plants, like people, need a community of friends to keep them healthy, well-watered, and their roots strong and sturdy. The idea is to dramatically slow down the growth of the weeds, then plant your crops—so your garden will have a good head start.

In order to provide your crops a proper amount of water, you may want to build little mounds in a wet area so as to allow your crops to keep drier, or little pits in the ground for a dry climate to allow water collection. You can make use of the Native American Seven Sisters garden as mentioned in previous issues of this magazine, Spanish Dehesa farming, Climate Farming, Forest Gardening, Permaculture, and Natural Farming (invented by Masanobu Fukuoka in his excellent book The One-Straw Revolution). Whatever method or mix of methods you choose, all of the above mentioned types of farming require no tilling, which is a big part of Landmedicine as tilling is extremely destructive for a host of reasons. The general idea is to plant diverse and all-purpose crops, hopefully planting some native plants as well. Fiber producing plants like hemp, vegetables, vines, berry bushes, nut trees, fruit trees, perennials, maybe even stevia for a natural sweetener and soapwort for a soap that grows in the garden—mimicking the layers of a forest. Seed-saving and animal breeding are also important because they keep your expenses down and allow your plants and animals to adapt to your specific landscape.

After planting crops,

you may want to build a fence around your garden to protect it from wildlife and whatever livestock you may choose to get. I like using existing trees for that purpose, weaving sticks in between the trees like wattle without the daub.

You may want to build water systems like the keyline technique (little trenches that collect water into a pond or wetland), sloughs, or swales (man-made wetland restoration). In order to provide your animals with free, natural, and mineral-rich water, you might consider creating a wetland from a spring, digging a pond, or even digging a well and filling up a trough thereby.

Get some livestock (if you haven’t already) from a farmer, breeder, auction, etc. Then introduce them to the forest pasture. A livestock guardian dog, such as a Great Pyrenees, will help protect your animals from predators. You can let the chickens roost up in the trees or you can build them a simple coup to protect them. The same for all your livestock, but remember to build a natural building that won’t introduce harmful chemicals into your Land or animals. A stone pen for goats does fine, or whatever you may choose.

Many people use a compost pile, but easier than that is simply throwing all your natural waste into the garden to add humus and nutrients. You can throw rotten vegetables, meat, bones, manure, and even pottery shards. To be honest, Amazon tribes also put humanure (their own poop) in their gardens—it’s up to you though! The charcoal in the plot will absorb the nutrients and prevent them from washing away. Every year, if you choose, you can move your garden plot to a new spot, ensuring that you don’t deplete the nutrients—in fact, you’ll increase the nutrients in your forest and beautify your Land.

In conclusion,

Landmedicine is an easy and effective method I highly encourage. I aim to discuss plenty more interesting topics with y’all in the future. I wish y’all the very best in your goal to live in harmony with Nature!

Credit: Mother Earth News Magazine